Wife of African American Author William Wells Brown

On April 12, 1860 twenty-five year old Anna Elizabeth Gray married William Wells Brown – author of Clotel, the first novel written by an African American in the United States. Anna later published Brown’s works under the imprint A.G. Brown. They had one daughter, Clotelle, in 1862.

On April 12, 1860 twenty-five year old Anna Elizabeth Gray married William Wells Brown – author of Clotel, the first novel written by an African American in the United States. Anna later published Brown’s works under the imprint A.G. Brown. They had one daughter, Clotelle, in 1862.

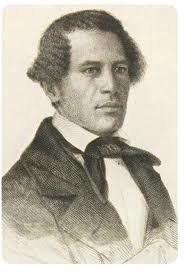

William Wells Brown (1814-1884) was a prominent African American abolitionist lecturer, novelist, playwright and historian. After spending the first 25 years of his life in slavery and most of a decade on the run as a fugitive, Brown came into prominence in the abolitionist movement. He wrote his autobiography, several volumes of black history and Clotel, the first novel written by an African American. Although he published more than a dozen books and pamphlets, Brown has been generally ignored in American history.

William Wells Brown was born in 1814 on plantation near Lexington, Kentucky. His mother was a slave and his father, George Higgins, was a white planter who was a cousin of his mother’s owner, Dr. Thomas Young. His mother gave birth to seven children by seven different fathers.

Although Young promised his cousin he would never sell the boy (whom Higgins recognized as his son), William was sold multiple times before he was twenty years old. Dr. Young moved to Missouri and worked as a physician, miller, merchant and raised tobacco and hemp. William was raised to be a house slave while his mother worked in the fields.

William spent most of his youth in St. Louis. His masters hired him out to work on the Missouri River, then a major thoroughfare for steamships and the slave trade. Brown was incensed when his owner sold him, and even worse, his sister Elizabeth had been sold by her owner to man in Natchez, Mississippi. Brown decided to make an escape attempt and persuaded his mother to join him. Both were captured in Illinois and returned to St. Louis after their owners posted a $200 reward.

William’s mother was taken to the slave markets of New Orleans to be sold, and Brown was sold to a merchant tailor Samuel Willi, who contracted William out for a while before selling him to another steamboat captain, Enoch Price.

On a journey with Captain Price and his family to Ohio, a free state, William escaped on New Year’s Day of 1834, when he slipped away from a steamboat while it was docked in Cincinnati. He later wrote that on his last day of bondage:

[I] imagined I saw my dear mother in the cotton-field, followed by a merciless taskmaster, and no one to speak a consoling word to her! I beheld my dear sister in the hands of a slave-driver, and compelled to submit to his cruelty! None but one placed in such a situation can for a moment imagine the intense agony to which these reflections subjected me.

He adopted the name of Wells Brown, a Quaker friend, who helped him after his escape by providing food, clothes and money. He spent the next two years working on a Lake Erie steamboat and helping fugitive slaves escape into Canada as a conductor for the Underground Railroad.

In the summer 1834, Brown met and married Elizabeth Schooner, a free African American woman, and they had three daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth.

In 1836, Brown moved to Buffalo, New York, where he began his career in the abolitionist movement by regularly attending meetings of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, by boarding antislavery lecturers at his home and speaking at local gatherings and by traveling to Cuba and Haiti to investigate emigration possibilities.

Brown’s abolitionist career was marked by a turning point in the summer of 1843 when Buffalo hosted a national antislavery convention and the National Convention of Colored Citizens. Brown attended both meetings, sat on several committees, and became friends with other black abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and Charles Lenox Remond.

When the Liberty Party formed, Brown chose to remain independent, believing that the abolitionist movement should avoid becoming entrenched in politics. He continued to support the Lloyd Garrison’s approach to abolitionism, and shared his own experiences and insight into slavery in order to convince others to support the cause.

Due to Brown’s service in the antislavery movement, sophistication as a speaker and his growing reputation in the antislavery community, he was invited to lecture before the American Anti-Slavery Society at its 1844 annual meeting in New York City. In May 1847, he was hired as a Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society lecture agent, and moved to Boston.

In 1847, he published his memoir, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself, which became a bestseller second only to Frederick Douglass’ slave narrative. He critiques his master’s lack of Christian values and the brutal use of violence in master-slave relations.

By 1849 Brown was separated from his wife, and he left the United States to travel in the British Isles to lecture against slavery to build support for the U.S. movement. He also wanted to learn more about the cultures and religions of European nations. In his memoir he wrote, “He who escapes from slavery at the age of twenty years, without any education, must read when others are asleep, if he would catch up with the rest of the world.”

In 1849 Brown was invited by Victor Hugo to speak the International Peace Conference in Paris. Afterwards Brown was feted at a reception hosted by Alexis de Tocqueville. He stated that the only disapproval he felt as a Black man in France came from United States Ambassador Richard Rush, son of Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and his daughters.

Still lecturing in England when the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law was passed in the U.S., Brown stayed on to avoid risk of capture and re-enslavement. After his freedom was purchased by a British couple in 1854, he returned to the U.S. and quickly joined the abolitionist lecture circuit again.

When Brown returned to the United States, he had written his first novel: Clotel, or, The President’s Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States, the first novel written by an African American. It is also the first novel published by an African American, but because it was published in England it was not the first African American novel published in the United States. Clotel is an imagining of the fate of the children produced by Thomas Jefferson and his slave Sally Hemings.

Brown was a pioneer in several different literary genres, including travel writing, fiction and drama. Based on this journey abroad, Brown also wrote Three Years in Europe: or Places I Have Seen And People I Have Met. The publication of those works as well as a play and a compilation of antislavery songs established his reputation as the most prolific African-American writer of the mid-nineteenth century.

Brown was also in the process of writing St. Domingo, a work that suggests that more militant actions were needed to help the abolitionist cause. Perhaps because of the rising social tensions in the 1850s, he became a proponent of African-American emigration to Haiti, an independent black republic. He also advocated equal rights for women and the temperance movement.

Image: William Wells Brown

Most scholars agree that Brown is the first published African American playwright. He wrote two plays, Experience; or, How to Give a Northern Man a Backbone (1856) and The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom (1858), which he sometimes read aloud at abolitionist meetings.

Elizabeth Schooner Brown had died while William was in Europe. On April 12, 1860, Brown married twenty-five year old Anna Elizabeth Gray, who later published Brown’s works under the imprint A.G. Brown. They had one daughter, Clotelle, in 1862.

During the Civil War Brown continued to publish fiction and non-fiction books, and played an active role in recruiting blacks to fight in the war. He introduced Robert John Simmons from Bermuda to abolitionist Francis George Shaw, father of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the commanding officer of the all African American 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Brown preached against the doctrine of racial inferiority calling black people to respect their heritage and strive for self-improvement through hard work. On the night of January 1, 1863, William Wells Brown was one of the dignitaries who gathered in Tremont Church in Boston awaiting word of President Abraham Lincoln‘s Emancipation Proclamation.

During the remainder of his life, Brown lived in the Boston area and produced three major volumes of black history: The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863), The Negro in the American Rebellion (1867) [considered the first historical work about black soldiers in the Civil War] and The Rising Son (1873).

As slavery ended, Brown’s career as a traveling speaker slowed. During the last ten years of his life, he continued to travel, lecture and write. He completed his last book, another volume of autobiography, My Southern Home: Or, the South and Its People, in 1880.

The author also studied homeopathic medicine and opened a medical practice in Boston’s South End while keeping a residence in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until moving to the nearby city of Chelsea in 1882.

Brown continually struggled with how to represent slavery “as it was” to his audiences. At an 1847 lecture to the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem, Massachusetts, he said:

Were I about to tell you the evils of Slavery, to represent to you the Slave in his lowest degradation, I should wish to take you, one at a time, and whisper it to you. Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented.

William Wells Brown died in Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1884 at the age of 68. He is buried in an unmarked grave in the Cambridge Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There is no information available about the remainder of Anna’s life.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: William Wells Brown

BlackPast.org: William Wells Brown

Documenting the American South: William Wells Brown