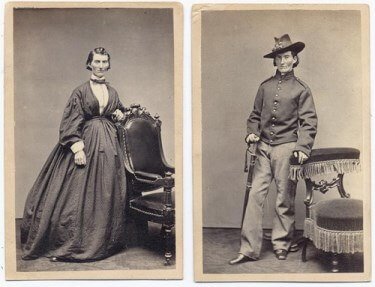

Woman Soldier in the Civil War

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman disguised herself as a man in order to fight for the Union in the Civil War. The letters she wrote home were preserved by her family, but were not made public for nearly a century because they were stored in the attic of one of her relatives.

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman disguised herself as a man in order to fight for the Union in the Civil War. The letters she wrote home were preserved by her family, but were not made public for nearly a century because they were stored in the attic of one of her relatives.

Wakeman, most often referred to as Rosetta, was born on January 16, 1843, in Afton, New York, to Harvey Anable and Emily Wakeman. She worked hard on her father’s dairy farm to help support her family, and later worked as a domestic. Her father served as town constable, but was deeply in debt.

At the age of 19, Rosetta left home and traveled to the nearest large city, Binghamton, New York, looking for work. She soon realized that she could make more money by disguising herself as a man. She was hired as a boatman on a coal barge, and sent most of her earnings back to her family.

On her first trip up the river, Rosetta met several soldiers from the 153rd New York Regiment of Volunteers, who told her they had received a $152 signing bonus and were earning $13 a month in pay. Army recruiters assumed she was a male and asked her to join.

She used the name Lyons Wakeman, and claimed to be 21 years old. She was accepted into the regiment on August 30, 1862. The description on her enlistment papers said that she was five feet tall, fair-skinned, with blue eyes. The regiment was sent to Washington DC, in October 1862, where they remained for nine months, defending the nation’s capital against rebel advances. Rosetta wrote home saying, “I can drill as good as any man in my regiment.”

Wakeman’s first letter home was sent on November 24, 1862. In the letter, she explained what she did after she left home, and how she ended up as part of the Union Army. She began sending money home, and attempted to mend any broken fences with her comment: “I want to drop all old affray and I want you to do the same and when I come home we will be good friends as ever.” Interestingly enough, she signed her early letters with her birth name, making no attempt to hide her identity in case her letters were intercepted.

In her letters, Rosetta expressed her strong religious faith, the pride she felt at being a good soldier, and her strong desire to be financially independent, a dream that was shared by many nineteenth-century women. She was outspoken, independent, and hoped to buy a farm of her own after the war.

In February 1864, her unit was sent to Louisiana to take part in General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign. Rosetta experienced battle up close for the first time in April 1864.

By April 1864, Major General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign had advanced about 150 miles up Red River. Major General Richard Taylor (son of President Zachary Taylor), commander of the Confederate forces in the area, decided that it was time to try and stem this Union drive. On April 8, Taylor fought to a victory at the Battle of Mansfield or Sabine Crossroads.

Battle of Pleasant Hill

The bulk of the Federal army came back together at Pleasant Hill. Banks then decided to withdraw to Grand Ecore, while leaving a strong rearguard at Pleasant Hill. This force probably numbered around 11,000 men. To oppose it, Taylor now had close to 13,000 men, having been reinforced by two divisions late on April 8.

Early on April 9, 1864, Taylor’s forces marched toward Pleasant Hill in the hopes of finishing the destruction of Banks’ army. Taylor felt that the Yankees would be timid after Mansfield and that an audacious, well-coordinated attack would be successful. The Confederates closed up, and rested for a few hours.

At 5:00 pm, Taylor launched a vigorous attack, which met with some initial success. He planned to send a force to assail the Union front while he rolled up the left flank and moved his cavalry around the right flank to cut off the escape route.

The attack on the Union left flank, under the command of Brigadier General Thomas Churchill, succeeded in sending those enemy troops fleeing for safety. Churchill ordered his men ahead, intending to attack the Union center from the rear. Union troops, however, discerned the danger and hit Churchill’s right flank, forcing a retreat. By the end of the day, only one Confederate division remained intact.

Of the deceased soldiers Rosetta wrote, “sometimes in heaps and in rows… with distorted features, among mangled and dead horses, trampled in mud, and thrown in all conceivable sorts of places. You can distinctly hear, over the whole field, the hum and hissing of decomposition.”

Pleasant Hill was the last major battle of the Louisiana phase of the Red River Campaign. Although Banks won, he retreated toward Grand Ecore, wishing to get his army out of west Louisiana before any greater calamity occurred.

Image: Battle of Pleasant Hill Re-enactment

Image: Battle of Pleasant Hill Re-enactment

Each April, re-enactments of battles, field medical services and a war-time marriage ceremony are among events held. Has over 700 participants and attracts between 5,000 and 10,000 visitors.

Rosetta wrote her last letter home on April 14, 1864, five days after the battle:

Our army made an advance up the river to Pleasant Hill about 40 miles. There we had a fight. The first day of the fight our army got whip[ped] and we had to retreat back about ten miles. The next day the fight was renewed and the firing took place about eight o’clock in the morning. There was a heavy Cannonading all day and a Sharp firing of infantry. I was not in the first day’s fight, but the next day I had to face the enemy bullets with my regiment. I was under fire about four hours and laid on the field of battle all night. There was three wounded in my Co. and one killed.

I feel thankful to God that he spared my life, and I pray to him that he will lead me safe through the field of battle and that I may return safe home.

Near the end of the Red River Campaign, drinking water became scarce, and Rosetta and her fellow soldiers drank from streams that were poisoned by the rotting flesh of dead animals. The connection between contamination and infection wasn’t understood at that time. The Union soldiers were stricken by chronic diarrhea, and died by the thousands.

Rosetta fell sick and was admitted to the regimental hospital at Alexandria, Louisiana, on May 3, 1864. When her condition worsened, she was transferred again to a Federal hospital in New Orleans on May 22. The trip south was fraught with problems. By the time she reached her destination, she was in the acute phase of dysentery. Her illness persisted, slowly draining the life from her.

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman died on June 19, 1864. If the nurses or doctors there discovered her true gender, they did not report it. She was buried as a soldier at the Chalmette National Cemetery in New Orleans. Her headstone reads, “Pvt. Lyons Wakeman.”

Many years later, Rosetta’s letters were discovered by a relative in the attic of the farmhouse where Rosetta grew up, in upstate New York. They were published in 1994 by editor Lauren Cook Burgess as An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, alias Pvt. Lyons Wakeman, 153rd Regiment, New York State Volunteers, 1862-1864. It wasn’t until then that the military discovered she was a woman.

In 1994, on the 130th anniversary of Rosetta Wakeman’s death, historians and Civil War buffs gathered for a reception in her honor followed by a visit to her grave at Chalmette National Cemetery, where she is buried in Section 52, Grave No. 4066.

Chalmette National Cemetery

Chalmette National Cemetery

New Orleans, Louisiana

Rosetta Wakeman was one of my earliest posts for the Civil War Women Blog, and I have wanted to update my original article since I learned that the red brick fences around the cemetery she is buried in were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina (the red bricks are piled up in the background). I live on the southwest Florida Gulf Coast, and suffered through many of those violent storms in the mid-2000s, the largest being Hurricane Charley in August 2004. Of course, I was relieved when Katrina took a northerly tack, but I never dreamed it would devastate such a beautiful old city as New Orleans.

SOURCES

Legends of America

Battle of Pleasant Hill

A Graver’s Journal: Chalmette National Cemetery

Battle Reenactment and Living History: The Battle at Pleasant Hill

I recently learned that Sarah Rosetta Wakeman is my 5th cousin five times removed. A tenuous connection but valid none the less.

I lived for 18 years in the same neighborhoods that she lived in. I felt at home the minute I moved there. Maybe this is why.