Wife of Confederate General Joseph Brevard Kershaw

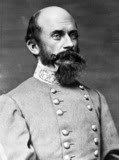

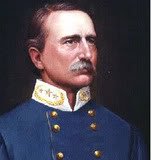

Image: General Joseph Kershaw

Image: General Joseph Kershaw

Lucretia Ann Douglas was born on August 27, 1825, the daughter of James and Mary Martin Douglas of Camden, South Carolina. Joseph Brevard Kershaw was born on January 5, 1822, son of John and Harriet DuBose Kershaw, also of Camden. His maternal grandfather, also named Joseph Kershaw, served on Francis Marion’s staff during the Revolutionary War. His father, who died when he was seven years of age, was several times mayor of Camden, a Judge, a Legislator, and a member of Congress. Kershaw attended first a school in Camden; he was sent at the age of fifteen to the Cokesbury Conference school, in Abbeville District.

Leaving school, after a short visit home, Kershaw went to Charleston, SC, where he became a clerk in a dry goods store. Unhappy with that life, he returned to Camden and entered as a student in the law office of John DeSaussure. Kershaw was admitted to the bar at the age of twenty-one, and soon afterwards formed a partnership with James Pope Dickinson.

Joseph Kershaw married Lucretia Douglas in November 1844, and they had nine children.

Kershaw joined the Palmetto Regiment in the Mexican War, and was elected First Lieutenant of the Camden company, known as the DeKalb Rifle Guards. His law partner, James Dickinson, was subsequently killed at the battle of Cherubusco in the war with Mexico, gallantly leading the charge of the Palmetto Regiment.

Kershaw contracted a fever and returned home to Camden a very sick man. He resigned his commission and Lucretia nursed him back to health. Upon the recovery of his health, he resumed the practice of law in Camden. He was elected to the State Legislature in 1852 and 1854, and became active in the Militia in 1859; he was a member of the Secession Convention from his district, which led to South Carolina seceding from the Union.

The Civil War

Joseph Kershaw was the embodiment of the Confederate gentleman-turned-soldier ideal, a lawyer from the Cradle of the Rebellion, South Carolina. He was intelligent, literate, and dignified, a man of high character. Blond, with refined features and a resolute expression, he was clean-shaven except for a drooping blond mustache. He had the bearing of command and a clear voice that seemed to inspire courage.

Kershaw stood about 5’10” with posture as straight as an arrow. His chief physical characteristics that his contemporaries commented upon were his beautiful deep blue eyes and a clear voice that he understood how to use effectively. When he went off to war, Lucretia made herself a necklace and bracelet woven from locks of his hair.

Early in 1861, by command of Governor Pickens, Kershaw led his unit to Charleston, and they were onMorris Island during the siege of Fort Sumter. There they remained until called to go to Virginia to enter the Confederate Army. They were joined by other companies which offered their services, and the new regiment, now known as the Second South Carolina Volunteers, proceeded to Richmond.

Kershaw’s regiment was assigned to General Milledge Bonham. They fought on Henry House Hill at First Manassas, and played a major role in breaking the Union lines and chasing the Yankees back to Washington. After General Bonham resigned in a huff over a seniority dispute, Kershaw was appointed Brigadier General and took command of Bonham’s brigade.

On the Peninsula the next summer, Kershaw led his brigade in action at Williamsburg, Malvern Hill, and Savage Station during the Seven Days’ Battles. In division commander General Lafayette McLaws’ official report after those battles, he wrote: “I beg leave to call attention to the gallantry, cool, yet daring, courage and skill in the management of his gallant command exhibited by Brigadier General Kershaw.”

Thus there was already much expected of Kershaw and and his men before the Maryland Campaign in September, where Kershaw’s men forced Union soldiers off the critical Maryland Heights before the capture of Harper’s Ferry. There, some of the men had to load and fire from positions where they had to use one arm to keep from rolling down the mountainside. After the Battle of Sharpsburg, Kershaw was again highly praised by McLaws.

At Fredericksburg, Kershaw had his finest hour, reinforcing General Thomas Cobb’s brigade behind the Stone Wall on Marye’s Heights and taking command when Cobb was mortally wounded. Leading his brigade on horseback, Kershaw emerged on the crest of the hill a conspicuous and defiant target. It was said later that when he reined in his horse, the Yankees withheld their fire as if out of respect, and that Kershaw took off his cap in acknowledgment before he disappeared behind the bastion of the Stone Wall. At Chancellorsville, Kershaw was not heavily engaged.

Image: Valor in Gray

Image: Valor in Gray

Mort Kunstler, Artist

Kershaw’s Brigade at Fredericksburg December 13, 1862

General Joseph Kershaw is seen in the painting, mounted on horseback between two of his aides. Advancing in battle lines up the hill toward them was the mighty Army of the Potomac – more than 115,000 strong – composed of courageous, well-trained combat troops under the command of General Ambrose E. Burnside. Despite their numerical superiority, Kershaw held his brigade steady and poured forth a terrible fire from behind the stone wall.

Battle of Gettysburg

By the summer of 1863, General Kershaw, forty-one years old, had been a brigadier for a year and a half, and had distinguished himself in almost every battle General Lee’s army had fought. Kershaw showed an ability for quick rational decisions. His brigade was always well put in, and he never endangered his men rashly. General McLaws had complete faith in him and his brigade, and he was much admired by his South Carolinians. The official reports Kershaw wrote are graceful, literate, and restrained. He was a man who passed among the whistling bullets and shrieking shells with a calm center, never losing his dignity.

General Kershaw at the Rose Farm

General Lafayette McLaws arranged his division on Warfield Ridge — two lines of two brigades each: left front, facing the Peach Orchard, the brigade of Brigadier General William Barksdale; right front, Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw; left rear, Brigadier General William Wofford; right rear, Brigadier General Paul Jones Semmes.

The area known as the Wheatfield had three geographic features, all owned by the John Rose family: the 20-acre wheatfield, Rose Woods bordering it on the west, and a modest elevation known as Stony Hill, also to the west. Thirty cannons of the Union III Corps and the Artillery Reserve were tasked with holding this section and were positioned along Wheatfield Road.

Around 5:00 pm, CSA General James Longstreet ordered McLaws to send in Kershaw’s Brigade, with Barksdale’s to follow on the left, beginning an en echelon attack — one brigade after another in sequence — which would be used for the rest of the afternoon. Nearly 2200 South Carolinians stepped out of the woods on Warfield Ridge.

After taking losses from the Union batteries along Wheatfield Road while crossing the fields, the South Carolinans crossed the Rose Farm, and headed toward the Union troops on Stony Hill. By 5:30 pm, when the first of Kershaw’s regiments neared the Rose farmhouse, Stony Hill had been reinforced by two Union brigades. Kershaw’s men placed great pressure on them, but they continued to hold.

The fighting swelled to a crescendo and raged steadily for an hour, when the Union troops began to pull out. One division was withdrawn about 300 yards to the north to a new position near the Wheatfield Road. The second Union division followed suit, and the Confederates seized Stony Hilland streamed into the Wheatfield.

While the right wing of Kershaw’s brigade attacked in the Wheatfield, its left wing wheeled left to attack the right flank of USA General David Birney’s line, where thirty guns from the III Corps and the Artillery Reserve attempted to hold the sector. Suddenly someone unknown shouted a false command, and the attacking regiments turned to their right, toward the Wheatfield, which presented their left flank to the batteries. Kershaw later wrote, “Hundreds of the bravest and best men of Carolina fell, victims of this fatal blunder.”

A determined Kershaw threw his men back into the attack, reinforced with a Georgia Brigade under Brigadier General Paul Semmes. Semmes led two of his regiments into a gap on Kershaw’s right in the lower part of the wheatfield, where General Semmes was mortally wounded, and his men were counterattacked by a fresh Union brigade under Colonel John Brooke. At the point of the bayonet, Brooke’s small regiments drove Semmes’ men back to the Rose Farm orchards south of the house, and the two sides fought it out in a seesaw struggle.

At about 7:30 pm, the final Confederate assault through the Wheatfield continued past Houck’s Ridge. The brigades of Anderson, Semmes, and Kershaw were exhausted from hours of combat in the summer heat and advanced east with units jumbled up together. As they reached the northern shoulder of Little Round Top, they were met with a counterattack from the V Union Corps, which drove the Confederates back beyond the Wheatfield to Stony Hill.

The fighting was hand to hand for awhile and very intense, and involved numerous confusing attacks and counterattacks over two hours by eleven brigades. Veterans compared it to a whirlpool – a stream of eddies and tides that flowed around the Wheatfield, which changed hands six times that afternoon.

Charge and counter charge left the Wheatfield and nearby woods strewn with more than 4000 dead and wounded Union and Confederate soldiers. The bloody Wheatfield remained quiet for the remainder of the battle, but it took a heavy toll; the Confederates suffered 1394 casualties, and the Union 3215. Some of the wounded managed to crawl to Plum Run but could not cross; the stream ran red with their blood.

General Kershaw’s Description of July 2, 1863

Twenty years after the battle, there was an ongoing debate as to why the Confederacy had lost at Gettysburg. In reply to the many critics and notions of military mismanagement, an aged Kershaw wrote a brief article for Century Magazine on his brigade’s participation in this monumental battle – a bit difficult to follow at times, but well worth the read:

My brigade, composed of South Carolinians, constituted, with Semmes’s, Wofford’s, and Barksdale’s brigades, the division of Major General Lafayette McLaws. About sunset on the 1st of July, we reached the top of a range of hills overlooking Gettysburg, from which could be seen and heard the smoke and din of battle then raging in the distance. We encamped two miles from Gettysburg, on the left of the Chambersburg Pike.

On the 2d [of July], we were up and ready to move at 4 am in obedience to orders, but, owing as we understood at the time to the occupancy of the road by trains of the Second Corps, did not march until about sunrise. With only a slight detention from trains in the way, we reached the high grounds near Gettysburg and moved to the right of the Third Corps, [my] brigade being at the head of the column.

At length, General McLaws ordered me to move by a flank to the rear, get under the cover of the hill, and move along the bank of Marsh Creek toward the enemy, taking care to keep out of their view. In executing this order, we passed the Black Horse Tavern and followed the road leading from that point toward the Emmitsburg Pike, until the head of the column reached a point where the road passed over the top of a hill, from which our movement would have been plainly visible from the Federal signal station at Little Round Top.

Here we were halted by General McLaws in person, while he and General Longstreet rode forward to reconnoiter. Very soon those gentlemen returned, both manifesting considerable irritation, as I thought. General McLaws ordered me to countermarch and in doing so we passed Hood’s division, which had been following us. We moved back to the place where we had rested during the morning and thence by a country road to Willoughby Run… and down to that school house beyond Pitzer’s [farm].

General Longstreet here commanded me to advance with my brigade and attack the enemy at the Peach Orchard, which lay a little to the left of my line of march, some six hundred yards in front of us. I was directed to turn the flank of that position, extend my line along the road we were then in beyond the Emmitsburg Pike, with my left resting on that road. At 3:00 pm, the head of my column emerged from the woods and came into the open field in front of the stone wall which extends along by Flaherty’s farm and to the east past Snyder’s [farm].

Here we were in full view of the Federal position. An advanced line occupied the Peach Orchard, heavily supported by artillery, and extended from that point toward our left along the Emmitsburg Road. The intervening ground was occupied by open fields, interspersed and divided by stone walls. I immediately formed line of battle along the stone wall… done under cover of my skirmishers, who engaged those of the enemy near the Emmitsburg Road.

Image: The Rose Farm

Photo taken from the Wheatfield RoadIn the meantime I examined the position of the Federals with some care. I found them in superior force, strongly posted in the Peach Orchard, which bristled with artillery, with a main line of battle in their rear… and extending to if not upon, Little Round Top. I placed my command in position under cover of the Stone Wall, and communicated the condition of matters to Major General McLaws.

The division was then formed on this line, Semmes’s brigade two hundred yards in rear and supporting Kershaw’s; Barksdale’s on the left of [mine] with Wofford’s in Barksdale’s rear supporting him. Cabell’s battalion of artillery was placed along the wall to [my brigade’s] right, and the 15th South Carolina Regiment, Colonel [William] de Saussure, was thrown to their right to support them on that flank.

In the meantime General Hood’s division was moving in our rear to the right, to gain the enemy’s left flank, and I was directed to commence the attack as soon as General Hood became engaged, swinging around the Peach Orchard, and at the same time establishing connection with Hood on my right, and cooperating with him.

In my center-front was a stone farmhouse [Rose Farm] with a barn also of stone. These buildings were about five hundred yards from our position and on a line with the crest of the Peach Orchard hill. The Federal infantry was posted along the front of the orchard, and also on the face looking toward Rose’s.

Six of their batteries were in position, three at the orchard near the crest of the hill, and the others about two hundred yards in rear… Behind Rose’s was a morass and on the right of that, a stone wall running parallel with our line, some two hundred yards from Rose’s. Beyond the morass was a stony hill covered with heavy timber and thick undergrowth, interspersed with boulders and large fragments of rock extending some distance toward the Federal line… [by] which a narrow road led in the direction of [Little Round Top]. Looking down this road from Rose’s, a large wheatfield was seen. In rear of the wheatfield… a heavy force of Federals [were] posted in line behind a stone wall.

About 4 o’clock, I received the order to move, at a signal from Cabell’s artillery. They were to fire for some minutes, then pause, and then fire three guns in rapid succession. At this time, I was to move without further orders. I communicated these instructions to the commanders of each of the regiments in my command, directing them to convey [these orders] to the company officers. They were told, at the signal, to order the men to leap the wall… and to align the troops in front of it.

The 3rd and 7th South Carolina took this position from General Barnes’ Federal Division. Barnes felt at the time his position was about to be turned, and fell back to the Wheatfield Road. In turn, Federals counterattacked with forces that included the famous Irish Brigade to wrestle the hill back, if only temporarily.

Accordingly, at the signal, the men leaped over the wall and were properly aligned; the word was given and the brigade moved off… with great steadiness and precision, followed by Semmes with equal promptness. General Longstreet accompanied me in this advance on foot as far as the Emmitsburg Road. All the field and staff officers were dismounted on account of many obstacles in the way.

When we were about the Emmitsburg Road, I heard Barksdale’s drums beat the assembly, and knew then that I should have no immediate support on my left. The 2nd and 8th South Carolina regiments and James’s [Third] Battalion constituted the left wing of the brigade and were then moving majestically across the fields to the left of the lane leading to Rose’s with the steadiness of troops on parade.

They were ordered to change direction to the left and attack the batteries in rear of the Peach Orchard, and accordingly moved rapidly on that point. In order to aid this attack, the direction of the 3rd and 7th regiments was changed to the left so as to occupy the Stony Hill and Wood.

After passing the buildings at Rose’s, the charge of the left wing was no longer visible from my position; but the movement was reported to have been magnificently conducted… when the order was given to ‘move by the right flank,’ by some unauthorized person, and was immediately obeyed by the men. The Federals… opened on these doomed regiments a raking fire of grape and canister at short distance, which proved most disastrous, and for a time destroyed their usefulness. Hundreds of the bravest and best men of Carolina fell, victims of this fatal blunder.

While this tragedy was being enacted, the 3rd and 7th regiments were conducted rapidly to the stony hill. In consequence of the obstructions in the way, the 7th regiment had lapped the 3rd a few paces, and when they reached the cover of the stony hill, I halted the line at the edge of the wood for a moment, and ordered the 7th to move by the right flank to uncover the 3rd Regiment, which was promptly done. It was, no doubt, this movement observed by some one from the left, that led to the terrible mistake which cost so dearly.

The… 7th and 3rd regiments advanced into the wood and occupied the stony hill, the left of the 3rd Regiment swinging around and attacking the batteries to the left of that position. Very soon, a heavy column moved in two lines of battle across the wheatfield to attack my position in such manner as to take the 7th Regiment in flank on the right. The right wing of this regiment was then thrown back to meet this attack.

I then hurried in person to General Semmes, then 150 yards in my right rear, to bring him up to meet the attack on my right and also to bring forward my right regiment, the 15th, commanded by Colonel W. deSaussure, which… was cut off by Semmes’s brigade. In the act of leading his regiment, the gallant and accomplished commander of the 15th had just fallen when I reached it. He fell some paces in front of the line, with sword drawn, leading their advance.

General Semmes promptly responded to my call, and put his brigade in motion toward the right, preparatory to moving to the front. While his troops were moving, he fell, mortally wounded. Returning to the 7th Regiment, I reached it just as the advancing column of Federals had arrived at a point some two hundred yards off, whence they poured into us a volley from their whole line and advanced to the charge. They were handsomely received and entertained by this veteran regiment, which long kept them at bay in front.

One regiment in Semmes’s brigade came at a double quick as far as the ravine in our rear, and checked the advance of the Federals in their front. There was still an interval on a hundred yards… between this regiment and the right of the 7th, and into this the enemy was forcing his way, causing my right to swing back more and more; still fighting, at a distance not exceeding thirty paces, until the two wings of the regiment were nearly doubled on each other.

The enemy… swung around and lapped my whole line at close quarters, and the fighting was general and desperate all along the line, and so continued for some time. These men were brave veterans who had fought from Bull Run to Gettysburg, and knew the strength of their position, and so held it as long as it was tenable. The 7th Regiment finally gave way, and I directed Colonel [David] Aiken to re-form it at the stone wall about Rose’s. I passed to the 3rd Regiment, then hotly engaged on the crest of the hill, and gradually swung back its right as the enemy made progress around that flank.

Semmes’s advanced regiment had given way. One of his regiments had mingled with the 3rd and amid rocks and trees, within a few feet of each other, these brave men, Confederates and Federals, maintained a desperate conflict. The enemy could make no progress in front, but slowly extended around my right.

Separated from view of my left… the position of the 15th Regiment being wholly unknown, the 7th having retreated, and nothing being heard of the other troops of the division, I feared the brave men around me would be surrounded by the large force of the enemy constantly increasing in numbers and all the while gradually enveloping us.

In order to avoid such a catastrophe, I ordered a retreat to the buildings at Rose’s. On emerging from the wood as I followed the retreat, I saw Wofford riding at the head of his fine brigade then coming in, his left being in the Peach Orchard, which was then clear of the enemy. His movement was such as to strike the stony hill on the left and thus turn the flank of the troops that had driven us from that position. On his approach, the enemy retreated across the Wheatfield, where, with the regiments of my left wing, Wofford attacked with great effect, driving the Federals upon and near to Little Round Top.

I rallied the remainder of my brigade and a portion of Semmes’s at Rose’s, with the assistance of Colonel [Moxley] Sorrel of Longstreet’s staff, and advanced with them to the support of Wofford, taking position at the stone wall overlooking the forest to the right of Rose’s house. Finding that Wofford’s men were coming out, I retained them at that point to check any attempt of the enemy to follow.

It was now near nightfall, and the operations of the day were over. That night, we occupied the ground over which we had fought, with my left at the Peach Orchard, on the hill, and gathered the dead and wounded – a long list of brave officers and men. Captain Cunningham’s company of the 2nd Regiment was reported to have gone into action with forty men, of whom but four remained unhurt to bury their fallen comrades. My losses exceeded 600 men killed and wounded – about one half the force engaged.

The next day, July 3, Kershaw’s men were withdrawn to the wall in Biesecker’s Woods, where they had formed for the attack the afternoon before. They saw no action during the final day of battle, and retreated with the remainder of Lee’s army on July 4, and crossed the Potomac River on July 14. Kershaw deservedly appeared on Longstreet’s list of those “most distinguished for the exhibition of great gallantry and skill” at Gettysburg.

After Gettysburg, Kershaw went west with General Longstreet, and at Chickamauga, Kershaw was given command of the brigade of General Benjamin Humphreys, in addition to his own brigade. On foot instead of horseback, in the dense woods on Snodgrass Hill, Kershaw could not possibly control eleven regiments. Repeated attacks failed, until the Federals slipped away under cover of darkness.

The brigade participated in the Knoxville and East Tennessee Campaigns before going into winter camp. General Longstreet brought court-martial charges against General McLaws for a fiasco which had occurred at Knoxville on November 29, 1863. Kershaw was in a tough position because he was friends with both of his superior officers. His written depositions reflect his support for McLaws in this affair. Although the charges were found to be false, McLaws was transferred, elevating Kershaw to the command of McLaws’ division.

Kershaw’s division, one of the best in the Army of Northern Virginia, consisted of his old South Carolina brigade, General Benjamin Humphrey’s Mississippi Brigade, and two fine Georgia brigades commanded by William Wofford and Goode Bryan.

Kershaw was made major general in May 1864, and was given permanent command of McLaw’s old division, which he commanded for the rest of the war, a proud exception – with Major Generals Wade Hampton and John Brown Gordon – to General Lee’s rule that a division commander must be a professionally trained soldier.

In 1864, Kershaw fought at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. He was with Longstreet when he was wounded by his own troops at the Wilderness, when Longstreet’s party were mistaken for Union cavalry. Kershaw’s cry of “Friends!” probably saved the lives of several of the commanding general’s staff.

He led his division during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign to the final battle at Cedar Creek, Virginia, in October 1864. The general rallied and withdrew his shattered command from the battlefield, and returned to the Richmond defenses in early December 1864. He remained in the Richmond area until Lee’s army withdrew on April 2, 1865.

At the disastrous Battle of Saylor’s Creek on April 6, 1865, three days before Lee surrendered at Appomattox, six Confederate generals – Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, Major Generals Kershaw and Custis Lee, Brigadier Generals D.M. DuBose, Semmes, Hunter, and Corse – were surrounded and captured with their respective commands, after a desperate struggle against immense odds. Kershaw’s division numbered in all about 6000 men. The captured officers were sent to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, where they remained in prison until some time in August 1865, when they were allowed to return to their respective homes.

Kershaw had been captured by General George Armstrong Custer‘s cavalry who took him to their chief. The Yankee general treated Kershaw kindly and that night shared blankets with the captured general. Eleven years later, upon learning of Custer’s death at the Little Big Horn, Kershaw wrote a lengthy account of his capture as a tribute to the fallen cavalry leader. Kershaw called news of Custer’s demise “heart rendering.”

After the fight of Saylor’s Creek, when General Kershaw and his companions were being taken back to Petersburg and thence to City Point to be shipped North [to prison], he spent a night at a farm house, then occupied as a field hospital and as quarters by the surgeons and attendants. They were South Carolinians, and were anxious to hear all about the fight. In telling of it the pride and love which he reposed in the old brigade received a wistful testimonial. It was then confronting Sherman somewhere in North Carolina. Its old commander said in a voice vibrant with feeling: “If I had only had my old brigade with me, I believe we could have held these fellows in check until night gave us the opportunity to withdraw.

Source: History of Kershaw’s Brigade, by D. Augustus Dickert

After being paroled, General Kershaw returned to Camden, where he resumed his legal career, and enjoyed a large and lucrative practice for many years. He was elected to the State Senate in the fall of 1865, and was later chosen President of the Senate. He was appointed Judge of the Fifth Circuit in 1877, a position which he held with distinguished honor for sixteen years.

Kershaw resigned his judgeship in 1893, as his health began to fail. The splendid health he had enjoyed for many years had been undermined slowly and insidiously by disease incident to a life that had borne the burdens of others, and had spent itself freely and unselfishly for his country and his fellowman, and it was evident to all that his days were numbered.

At his retirement party, some of his former soldiers as well as associates in the legal profession paid tribute to him. Three members of Kershaw’s 2nd South Carolina were also lawyers, and used the occasion to speak in glowing terms of Kershaw’s abilities as a military officer, his efforts to help the state during Reconstruction, and his integrity as a judge.

In his message to the General Assembly in 1893, Governor B.R. Tillman proposed Kershaw as the proper person to collect the records of the services of South Carolina soldiers in the Civil War, and to prepare a suitable historical introduction to the volume. The Legislature promptly endorsed the nomination and made an appropriation for the work. To this he gave himself during the two succeeding months, collecting data, and preparing to write the proposed introduction, but he would never complete it.

In the latter part of March 1894, he became alarmingly ill. All was done for his relief, but to no avail. Among his last words to his son were these, spoken when he was perfectly conscious of what was before him: “My son, I have no doubts and no fears.”

General Joseph Brevard Kershaw died just before midnight on April 12, 1894. He is buried in Camden’s Quaker Cemetery along with many of his soldiers from Kershaw County.

At his funeral, there was a general outpouring of people from the town and vicinity for many miles, who sincerely mourned the departure of their friend. The State was represented by the Governor and seven members of his official family.

Lucretia Douglas Kershaw died on April 28, 1902.

Image: Lucretia Douglas Kershaw Grave

Image: Lucretia Douglas Kershaw Grave

Quaker Cemetery

Camden, South Carolina

SOURCES

Joseph Brevard Kershaw

History of Kershaw’s Brigade

Battle of Gettysburg, Day 2

Wikipedia: Joseph B. Kershaw

Battle of Gettysburg, Second Day

Joseph Brevard Kershaw Biography

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General Joseph Brevard Kershaw

General Joseph Kershaw’s Brigade at the Rose Farm