Wife of Union General James Samuel Wadsworth

Mary Craig Wharton was born on August 24, 1814, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. James Samuel Wadsworth was born on October 30, 1807, to wealthy parents, James and Naomi Wolcott Wadsworth, at Geneseo, the seat of Livingston County, New York. The senior James Wadsworth and his brother William were among the earliest settlers in Western New York. They traveled by raft and ox cart from their home near Hartford, Connecticut, arriving in the wilderness that was to become Geneseo in June of 1790. In time, James Sr. became the owner of one of the largest portfolios of cultivated land in the state.

Mary Craig Wharton was born on August 24, 1814, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. James Samuel Wadsworth was born on October 30, 1807, to wealthy parents, James and Naomi Wolcott Wadsworth, at Geneseo, the seat of Livingston County, New York. The senior James Wadsworth and his brother William were among the earliest settlers in Western New York. They traveled by raft and ox cart from their home near Hartford, Connecticut, arriving in the wilderness that was to become Geneseo in June of 1790. In time, James Sr. became the owner of one of the largest portfolios of cultivated land in the state.

Young James Wadsworth was groomed to fulfill the responsibilities he would inherit. He received a thorough rudimentary education, then attended Harvard University and Yale University. Soon after graduating, he studied law in Albany, finishing his course in the office of the great statesman and lawyer, Daniel Webster. Wadsworth was admitted to the bar in 1833, but had no intention of practicing. He spent the majority of his life managing his family’s estate.

On May 11, 1834, James Samuel Wadsworth married Mary Craig Wharton of Philadelphia, and the young couple set sail for a European honeymoon. James and Mary had six children: Charles, Cornelia, Craig, Nancy, James, and Elizabeth.

Hartford House

While visiting England, James and Mary Wadsworth met the Marquis Hertford, and were so charmed by his Palladian style villa, that they that they persuaded the Marquis to give them a copy of the plans. They selected a beautiful site overlooking the valley and the building project began in 1834. The house was given the Americanized spelling of Hartford, perhaps in deference to the family’s Connecticut origins, and became their family home for almost thirty years.

A third floor was added in 1851 to accommodate their family of six children. The house has since been the home of Congressmen, Senators and diplomats, and is occupied by the General’s descendants to this day. Although a private residence, it is frequently opened to guests and the community for everything from family weddings to historical society house tours.

Out of a sense of noblesse oblige, James Wadsworth became a philanthropist and entered politics, first as a Democrat, but then as one of the organizers of the Free Soil Party, which joined the Republican Party in 1856. In 1861, he was a member of the Washington Peace Conference, an unofficial gathering of Northern and Southern moderates who attempted to avert war. But after war became inevitable, he considered it his duty to volunteer.

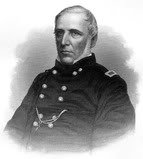

By the Civil War, James had taken his father’s place at the head of the wealthy family estate. Having no illusions about his military acumen, he led one of the first contingents of New York troops to Washington – chartering a ship at his own expense to get them there. He first served as a civilian volunteer aide on the staff of Union army commander Irvin McDowell, and was present at First Bull Run.

McDowell recommended Wadsworth for command, and even in the unabashed political free-for-all of the early-war army it must have raised a few eyebrows when he was jumped in rank all the way from volunteer aide-de-camp to brigadier general in August 1861. On October 3, he received command of the 2nd Brigade in McDowell’s Division of the Army of the Potomac, which he led until March 17, 1862.

From March 17 to September 7, 1862, General Wadsworth commanded the Washington defenses. During the preparations for Major General George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, Wadsworth complained to President Abraham Lincoln that he had insufficient troops to defend the capital due to McClellan’s plan to take a large number of them with him to the Virginia Peninsula.

On April 27, 1862, Wadsworth and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton laid out their conclusions about Washington’s inadequate defense in a night Cabinet meeting. As a result, Lincoln countermanded McClellan’s plan, and the corps commanded by Irvin McDowell was withheld from McClellan to defend Washington, generating ill feelings between Wadsworth and McClellan.

Historian Margaret Leech wrote:

From the outbreak of war, Wadsworth had been notable for his patriotism. At fifty-three, he was still lean and active. “Snowy hair and side whiskers framed his narrow, handsome face, and he wore the carved saber of antique pattern which his grandfather had carried in the Revolutionary War. To his new career of soldier, he had brought the qualities of energy, honor and courage. A landed proprietor of political interests, he resembled in many ways the Southern planters who had dominated Washington before 1861. There was one conspicuous difference.

Wadsworth was an ardent abolitionist, unsympathetic to the slaveholding population of the capital. From the moment of taking command, he showed an intense distrust of McClellan – who expressed the opinion that Stanton had inspired this antagonism. On the other hand, Major [William] Doster gathered from Wadsworth and his staff that there had been ill feeling for some months between the New Yorker and McClellan, because Wadsworth, officially and in conversation, had expressed himself in favor of an advance in Virginia.

General Wadsworth was notable for living in the same conditions as his men – and keeping a sharp eye for his soldier’s comfort and health. William O. Stoddard recalled a visit to Wadsworth’s military encampment in the fall of 1862. He noted that the general “is known as ‘Wadsworth of Geneseo,’ and he is about the richest brigadier in this army. When he is at home, he can ride up and down the Genesee, mile after mile, upon the lands of his own fair inheritance, and he is a gentleman of cultivated tastes, polished manners, and excellent mental capacity.”

When Stoddard found General Wadsworth’s camp, he was expecting something in line with the military exhibitions then in vogue. He wrote:

Is this Wadsworth’s headquarters? Only a little, old frame farmhouse. Very well, he can fix it up inside to suit himself. Mrs. Wadsworth is with him, and she is said to be a graceful, dignified, accomplished woman. She, too, was born rich, of a high-caste family, and she was a beauty and a belle in her day.

We are just in time to avoid keeping the General’s dinner waiting – that is, unless it is true, as it is said of him, that he would not really postpone it on account of anybody of less rank and importance than an attack in force by the Confederates.

Mary Wadsworth is at the head of the table, and she is admirable. The General is here. So are his staff, and several distinguished officers as guests, and the table is indeed brilliant! But it is of pine boards, without any cloth to cover it, and the dinner placed upon it consists rigidly of the regular army rations, well cooked, served in such ware as the private soldiers of Wadsworth’s brigade are eating from, around their campfires at this very hour.

After General McClellan left the Army of the Potomac, Wadsworth was appointed commander of the 1st Division, I Corps, on December 27, 1862, which he led until June 15, 1863. Wadsworth was widely admired in his new division because he spent considerable effort looking after the welfare of his men, making sure that their rations and housing were adequate. They were also impressed that he was so devoted to the Union cause that he had given up a comfortable life and served in the Army without taking any pay.

Wadsworth and his division’s first test in combat was at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, and his inexperience showed when he was ordered to cross the Rappahannock River below Fredericksburg. He waffled, first ordering the Iron Brigade down to the river in boats, then giving it up when they were fired on by Rebel marksmen on the opposite bank, then finally deciding to go ahead. They rowed across with only light casualties, Wadsworth himself swimming across on his horse just behind. Eventually, Hooker pulled the division back across the river, and the entire division was held uselessly out of the remainder of the battle.

Image: James Wadsworth Monument

Image: James Wadsworth Monument

Gettysburg National Military Park

The statue shows General Wadsworth as he stood with one arm extended directing his troops into battle. The statue was dedicated on October 6, 1914, designed by Edward P. Casey (base), sculptor was R. Hinton Perry, using Standard Bronze and Dark Barre Granite.

Wadsworth at Gettysburg

Wadsworth’s performance at the Battle of Gettysburg was much more substantial. He had been at the head of the division for about six months, and had only been lightly engaged during that time. He was a stout fighter, however, and was developing into a good general, evidenced by the fact that he was one of the few non-West Point division commanders retained when the army was reorganized the following year.

Wadsworth’s division was in the vanguard of Reynolds’ First Corps as it marched toward Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, 1863, and was the first Union infantry to reach the field. Between 11 o’clock in the morning and the fallback at 4 pm, Wadsworth’s men bore much of the brunt of the overwhelming Confederate attack that morning and afternoon west of the town.

Attacked on McPherson’s Ridge by CSA General Harry Heth’s Division as his men arrived, Wadsworth showed his inexperience in the first few moments when he withdrew part of Cutler’s brigade and left Hall’s Battery exposed, which made Hall pull his six guns out in such a hurry that a gun was lost. Hall was furious with Wadsworth. This mistake stemmed from Wadsworth’s ignorance of the proper use of artillery.

Once the shouting stopped, however, Wadsworth did a good job, swinging the right of his line back when CSA General Robert Rodes’ Division attacked from the north, then pulling back in good order to new positions on Seminary Ridge when the McPherson’s Ridge line was overlapped by the teeming enemy.

When the entire corps gave way that afternoon, Wadsworth and the remaining men of his two brigades withdrew to the north face of Culp’s Hill, where, mangled and disorganized as they were, they were enough to intimidate CSA General Richard Ewell and his lieutenants into calling off their attack at the bottom of the hill.

But by the time the division retreated back through town to Cemetery Hill that evening, it had suffered over 50% casualties – losing 2400 out of 4000 men. Wadsworth saw over half of division disappear – either left crumpled on the field or trudging sullenly toward enemy prison camps – but bought the time it took to gather the rest of the army on the formidable hills to the southeast.

An image which shows how completely Wadsworth identified with his men was provided by a messenger who rode by Wadsworth on the evening of this first day at Gettysburg:

We found General Wadsworth sitting on a stone fence by the roadside, his head bowed in grief, the most dejected woebegone person one would likely find on a world-around voyage–a live picture of Despair: General Reynolds killed, the first corps decimated a full half, and its first division almost wiped out of existence. The General greeted us warmly, adding, “I am glad you were not with us this afternoon.”

Despite these losses, on the second day of battle, Wadsworth’s division was assigned to the defense of part of Culp’s Hill. On the evening of July 2, just as the defenses of Culp’s Hill were being stripped to provide reinforcements for the embattled Federal left, Wadsworth sent three regiments to reinforce the brigade of General George S. Greene, which was holding the summit of the hill against CSA General Edward Johnson’s Stonewall Division. Thus, the thin Union force was able to hang onto the hill through the night. During the third days’ fighting, Wadsworth rendered good service in maintaining the heights on the right of the line.

General Wadsworth left the army on July 15, 1863, less than two weeks after Gettysburg. During an eight-month leave of absence, he inspected colored troops on duty in the Mississippi Valley, and made an extensive tour of inspection through the southern and western states. Upon his return, he was named commander of the 4th Division, V Corps, composed of troops from his old division and that formerly led by General Abner Doubleday. A number of his contemporaries were left without assignments when the army reorganized or were sent to minor assignment elsewhere.

Wadsworth at The Wilderness

At the start of Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign, Wadsworth was Grant’s oldest divisional commander at age 56, about nine years older than the next oldest. Wadsworth led his division in General Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps at the Battle of the Wilderness. On May 5, he was ordered to countermarch and help defend the left of the Union position. However, he had lost his direction in the dense underbrush and drifted to the north, exposing his left to a sudden and harsh attack, which also included the Union division next to him.

While endeavoring to rally his troops on May 6, 1864, the second day of the battle, Wadsworth was struck in the head by a bullet. He fell from his horse and was captured by Confederate forces that were pursuing his retreating men. Although unconscious, he lingered for two days.

General James Samuel Wadsworth died in a Confederate field hospital. His son-in-law, Montgomery Harrison Ritchie, who died only weeks later of disease contracted in battle, went into the Confederate camp to retrieve his body. Wadsworth’s remains were brought back to Geneseo, New York, and buried in Temple Hill Cemetery.

His death drew an outpouring of grief and recrimination from Navy Secretary Gideon Welles. He wrote in his diary, “No purer or more single-minded patriot than Wadsworth has shown himself in this war. He left home and comforts and wealth to fight the battles of the Union.” Horace Greeley, in his American Conflict, says : “The country’s salvation claimed no nobler sacrifice than that of James S. Wadsworth, of New York…. No one surrendered more for his country’s sake, or gave his life more joyfully for her deliverance.”

Wadsworth received a posthumous promotion to major general as of May 6, 1864, for his service at Gettysburg and the Wilderness.

General Wadsworth’s son, James Wolcott Wadsworth, Sr., and grandson, James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr., were successful New York politicians. His daughter Cornelia Wadsworth Ritchie Adair (1837-1921) became prominent as matriarch of Glenveagh Castle in County Donegal, Ireland, and the large JA Ranch in the Texas Panhandle.

Fort Wadsworth in South Dakota was named for him in 1864. Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, one of the defenses of New York Harbor, in the shadow of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, is also named for the general.

Mary Craig Wharton Wadsworth died on June 30, 1874.

Image: Wadsworth Monument

Image: Wadsworth Monument

Wilderness Battlefield

On County 621, a large block-stone pillar is a monument to General James S. Wadsworth, who was mortally wounded near this spot on May 6, 1864. Commander of the Fourth Division of General Gouverneur K. Warren‘s Fifth Corps, he was attacking the Confederate left flank when CSA General James Longstreet’s reinforcements broke through. Wadsworth’s grandson, a Congressman, erected this monument in 1936 near the spot where Wadsworth was shot.

SOURCES

James Wadsworth

The Other Hartford House

Wikipedia: James S. Wadsworth

James S. Wadsworth (1807-1864)

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General James Samuel Wadsworth