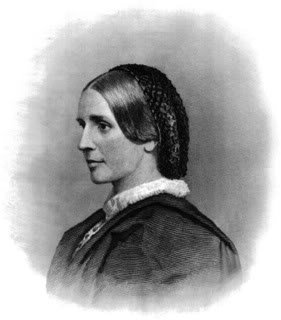

Wife of Union General John C. Fremont

Jessie Benton Fremont wrote many stories that were printed in popular magazines of the time as well as several books of historical value. Her writings, which helped support her family during times of financial difficulty, were mostly about the American West. She was outspoken on political issues and a determined opponent of slavery.

Jessie Benton Fremont wrote many stories that were printed in popular magazines of the time as well as several books of historical value. Her writings, which helped support her family during times of financial difficulty, were mostly about the American West. She was outspoken on political issues and a determined opponent of slavery.

The daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton and his wife, Elizabeth, Jessie Benton was born in Lexington, Virginia, but was raised in Washington, DC. Her father educated her as if she were his son, and taught her about American society and politics, introducing her to the leading politicians of the day.

Jessie was very close to her father, who shared with her the many books and maps in the valise that always accompanied him on their trips to and from Missouri and Virginia, and she began to share his dream of a nation stretching from ocean to ocean.

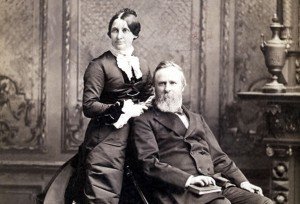

Seventeen-year-old Jesse was studying and living at Georgetown Seminary when she met and fell in love with Lieutenant John C. Fremont, who was ten years her senior. The couple eloped and were married on October 19, 1841. Senator Benton was so disappointed that he became estranged for a time from his daughter.

For a while after their marriage, Jessie and her husband lived on army posts. Senator Benton was persuaded by his ailing wife to accept the marriage, and a reconciliation occurred between Jessie and her father. The Fremonts then moved into the Benton home.

In 1842 John C. Fremont was assigned the task of exploring the West and scouting land for future US territorial expansion, which began the couple’s rise to fame. Fremont left his pregnant wife behind in the spring of 1842 to lead his first expedition to mark the trails West. He returned days before the birth of their eldest child, Elizabeth Benton “Lily” Fremont, who was born November 15, 1842 in Washington, DC.

Fremont then headed off again, and Jessie and the baby remained behind. Jessie was intensely interested in the details of his expedition, and became his recorder, making notes as he described his experiences. Adding human-interest touches to these printed reports, she wrote and edited best-selling stories of the adventures Fremont had while exploring the West with his scout, Kit Carson.

Through Jessie’s stories, John C. Fremont became famous as the Pathfinder to the West. And she involved herself in her life’s work: recording her husband’s experiences for a public eager for information about the opening of the West. Written during a time when the concept of Manifest Destiny was becoming increasingly popular, these narratives were received with great enthusiasm.

Jessie gave birth to a son, Benton Fremont, on July 24, 1848, in Washington, DC. The baby died within the year in St. Louis.

In 1849, Jessie and Lily made a harrowing journey aboard ship to join Fremont in California. After disembarking and crossing the Isthmus of Panama, they boarded another vessel to San Francisco. With income from their gold mines, the Fremonts established a home and settled into San Francisco society. Jessie became involved in city politics and discussed issues that were of importance at the time.

John C. Fremont served from September 1850 to March 1851 as Senator from California. Jessie gave birth to their third child, John C. Fremont, Jr. on April 19, 1851 at Las Mariposas, California. While the couple were visiting Paris, France, their fourth child, Anne Beverly Fremont, was born February 1, 1853. She died five months later. Their fifth and final child, Francis Preston Fremont, was born May 17, 1855.

In 1856, Jessie became the first presidential candidate’s wife to play an active part in a political campaign. She actively supported her husband’s antislavery platform and was an asset to his career and political goals. When Republican Party candidate Fremont’s name came up in rallies for votes, the slogan was “Fremont and Jessie too.” Fremont garnered many northern votes, but lost overall.

The Fremonts then moved to California where they discovered gold on their property. They settled into San Francisco society with Jessie leading the way and enjoying discussing politics with the many educated men in that city. When war became imminent, John Fremont returned East to get a new commission, and Jessie went with him.

In 1861, they returned to St. Louis when John was appointed commander of the Western Region. They shared the belief that St. Louis was unprepared for war, and both pressured Washington to send more supplies and troops. Jessie threw herself into the war effort, helping to organize a soldier’s relief society and becoming very active in the Western Sanitary Commission which provided medicine and nursing to soldiers injured in the war.

These endeavors were some of the few acceptable avenues of participation for women in the 1860s, but Jessie wanted more. She used her political expertise to make decisions for John and organized his military campaign to the extent that she was called “General Jessie” by his critics. In spite of Jesse’s help, Fremont was always in trouble, and her life was embroiled in the politics of the Civil War era.

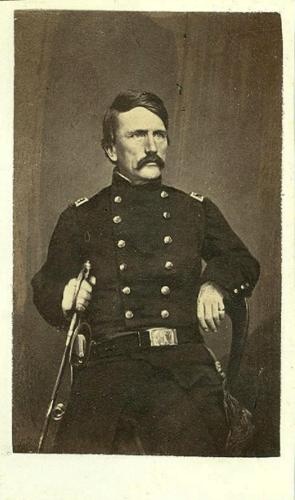

Fremont served as a major general in the Civil War, including a controversial term as commander of the Army’s Department of the West from May to November 1861. Fremont replaced William S. Harney, who had negotiated the Harney-Price Truce, which permitted Missouri to remain neutral in the conflict as long as it did not send men or supplies to either side.

Fremont had a deep hatred for slavery, but he overstepped his authority when he issued his own emancipation proclamation, which summarily freed all Missouri slaves. He neglected to confer with the President before issuing the order and Abraham Lincoln became angry with him.

Jessie, ever her husband’s protector, went to see President Lincoln in Washington to plead Fremont’s case. Lincoln listened but still removed Fremont from command. The Fremonts would not live in St. Louis again. They moved to New York and then California, where Jessie was that state’s first “First Lady.” Being unsuccessful in both places, John Fremont declared bankruptcy in 1873.

After the war, Jessie started writing books and articles about her adventures in the West to support the family, and remained committed to her husband, even when she heard rumors that he was being unfaithful.

In 1890, Fremont was involved in a controversial incident in California. Rather than being drummed out of the Army for insubordination, he was allowed to resign with his pension intact. Three months later John C. Fremont died in New York. He was buried in Rockland Cemetery, high atop the crest of the Palisades of the Hudson River just south of the Tappan Zee Bridge.

After the death of her husband, Congress granted Jessie a widow’s pension of $2000 a year. In 1891, she moved into a home in Los Angeles that was presented to her by a committee of ladies of the city as a token of their great regard. She remained in good health until about two and a half years before her death when an accident made her an invalid, but she was able to use a wheelchair and enjoy the outdoors.

In 1902, Jessie Benton Fremont, then a resident of the back-water pueblo of Los Angeles, died at age 78, and she was cremated and buried in Los Angeles at Angelus Rosedale Cemetery. Within the constraints of her era, she had demonstrated that women were capable of equal rights of citizenship and full participation with their male counterparts in family life, business and politics.

SOURCES

Jessie Benton Fremont

Wikipedia: Jessie Benton Fremont

Jessie Benton Fremont: Missouri’s Trailblazer

Far-West sketches, by Jessie Benton Fremont