Volunteer Confederate Nurses

American nursing was still in its infancy at the outbreak of the Civil War. In the antebellum South, women usually served as nurses within their own families. On large plantations, the master’s wife nursed her husband, children, and slaves. Many Southern women were already accustomed to caring for ill patients, and nursing was considered a woman’s duty.

American nursing was still in its infancy at the outbreak of the Civil War. In the antebellum South, women usually served as nurses within their own families. On large plantations, the master’s wife nursed her husband, children, and slaves. Many Southern women were already accustomed to caring for ill patients, and nursing was considered a woman’s duty.

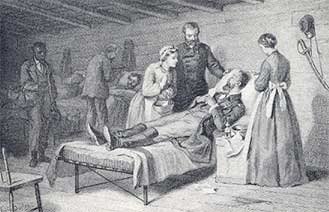

Image: Artist’s Sketch of a Civil War Hospital

Still, it was not a job that ladies of breeding and stature would volunteer for. The Southern woman was regarded as delicate and modest. When Fort Sumter was fired upon, and the wounded and dying came pouring in from the battlefields, the South found itself unprepared to care for its casualties.

The first nurses to serve the Confederacy were recuperating male soldiers, whose own illnesses prevented them from providing proper care. Plus, many of these men resented being appointed to hospital duty.

In response, the women of the South began to organize their own volunteer groups such as the Ladies’ Soldiers’ Relief Society and the Association for the Relief of Maimed Soldiers. Some women set up their own private hospitals in homes and donated buildings. The women of these organizations provided proper medical care for the wounded and ill soldiers of the Confederacy.

Southern nurses cleaned wounds, performed minor surgery, administered treatments and endured hard physical labor. They worked under deplorable conditions and had to fight off the infectious diseases that ran rampant through the hospital wards. Each nurse was expected to carry out a long list of nursing and non-nursing duties. They bathed patients, changed dressings on their wounds, distributed food and administered medications.

Nurses were also expected to beat and air out the straw mattresses their patients slept on, to change the straw in the mattresses every month and to scrub the floors in their ward. Some nurses were even pressed into service as hospital cooks. They built fires for cooking, washed patients’ faces, irrigated virulent wounds, and scrubbed underwear.

And they were expected to serve as a mother figure to the soldiers. They wrote letters for illiterate or handicapped patients and counseled them and their families. They had to always be feminine and cheerful.

As the war progressed, remote Southern towns were overwhelmed with the number of wounded coming in from the battlefields and were unprepared to care for them. But many Southern women had a strong desire to assuage the suffering of their protectors in the Confederate Army, despite the possibility of contracting debilitating and fatal infectious diseases.

Kate Cumming was born in Scotland and moved to Mobile, Alabama, while she was very young. In the spring of 1862, at age 26, she volunteered as a nurse, over the objections of her family, and at a time when many male doctors did not want women in their hospitals. Her writing reflected the horror encountered by some women in caring for the wounded.

Kate Cumming wrote:

The men are lying all over the house, on their blankets, just as they were brought in from the battlefield. They are in the hall, on the gallery, and crowded into very small rooms. The foul air from this mass of human beings at first made me giddy and sick, but I soon got over it. We have to walk, and when we give the men anything kneel, in blood and water, but we think nothing of it at all.

Cleanliness was virtually unheard of in Civil War hospitals. In the close, cramped quarters, “the smell of human waste, unwashed bodies, and gangrenous wounds was so intolerable as to overpower healthy men.” Nurses often had to put camphor-soaked cotton balls in their nostrils to avoid being overpowered by the smells. Many nurses died as a result of exposure to disease and filth.

When tending to an enemy prisoner of war, Southern nurses sometimes found it difficult to remain objective. Nurse Kate Cumming was confronted with this problem when she discovered that two Union POWs were in her ward. She wrote:

Before I went in, I thought I would be polite… but when I saw them laughing and apparently indifferent to the woe which they had been instrumental in bringing upon us, I could not help being indignant. [But] seeing an enemy wounded and helpless is a different thing from seeing him in health and power.

When the fighting drew near, nurses assisted in the evacuation of patients to safer locations. Emily Mason, present during the flight from burning Richmond in April 1865, wrote:

We led the way through the fire and smoke, our sleeves singed and our faces begrimed with sweat and dirt. My driver had become so unaccountably drunk that I could hardly hold him upon his seat.

Nursing in the Civil War South could be a harrowing experience, but with little or no training, the nurses who served the Confederacy made great contributions to the care of the sick and injured soldiers. They ventured into unsanitary hospitals to provide care to their countrymen, and quickly dispelled the myth of the fragile and timid Southern woman.

In a society dominated by men, these women carved a niche for themselves in nursing, proving that a woman’s compassion and strength need not be confined to home and family. And it took quite a woman to endure the sights and smells present in those hospital wards. In the process, they fostered a growing respect for nursing as a vocation.

Phoebe Yates Pember, a widow from South Carolina, moved to Richmond and served as a matron at the gigantic Chimborazo Hospital. She wrote:

In the midst of suffering and death, hoping with those almost beyond hope in this world, praying by the bedside of the lonely and heart stricken; closing the eyes of boys hardly old enough to realize men’s sorrows, much less suffer by man’s fierce hate, a woman must soar beyond the conventional modesty considered correct under different circumstances.

Chimborazo Hospital

During the summer of 1861, when the Federal troops advanced in force on Bull Run, General Joseph E. Johnston reported that 9000 men would have to be sent back to Richmond for admittance to hospitals before his army could proceed. The newly-appointed Confederate Surgeon-General Samuel Preston Moore had only 2500 beds.

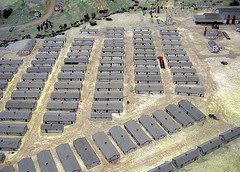

Image: Model of Chimborazo Hospital

Image: Model of Chimborazo Hospital

Chimborazo Hill was selected as the most favorable site for a hospital to care for the Confederate sick and wounded. It is east of Richmond on an elevated plateau of nearly forty acres and from the city by Bloody Run Creek. Early in 1862 the hospital was opened and in one week 2000 soldiers were admitted, and in two weeks’ time there were in all 4000.

In the end, there were 150 well-constructed and ventilated buildings, each one hundred feet in length, thirty feet in width, and one story high, built as needed to furnish comfortable quarters for the sick and wounded. Five large hospitals or divisions were organized; thirty wards to each division. The buildings were separated from each other by wide alleys, ample spaces for drives or walks, and a wide street around the entire hospital. It was the largest medical facility in the South during the Civil War.

The hospitals presented the appearance of a large town with its alignment of buildings whitened with lime, clean streets and alleys and a magnificent view of the surrounding countryside for many miles. The five hospitals were organized as far as possible on a State basis; troops from the same State being treated and cared for by officers and attendants from their own States.

In addition to the 150 buildings, there were 100 Sibley tents in which were put from eight to ten convalescent patients to a tent; these tents were pitched upon the slopes of the hill, presenting a very imposing sight. The total number of patients received and treated at Chimborazo Hospital amounted to 76,000 – about 17,000 were wounded soldiers. Of this number, approximately 6500 to 8,000 died.

With no model to draw on, Chimborazo Hospital’s success can be attributed to a combination of its open-air, pavilion-style design; the comparatively good quality of care; innovative practices; and the supreme dedication of the caregivers – men and women, black and white, slave and free. Their efforts contributed to one of the great advancements in mid-nineteenth-century medicine: the acceptance of hospital care for the sick and injured, which was a concept not embraced in America prior to 1865.