Sojourner Truth was an African American abolitionist and women’s rights activist who escaped from slavery in New York in 1826. She began as an itinerant preacher and became a nationally known advocate for equality and justice, sponsoring a variety of social reforms, including women’s property rights, universal suffrage and prison reform.

She was born Isabella Baumfree in 1797 on the estate of Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh in Swartekill, a Dutch settlement in upstate New York. She was one of 13 children born to Elizabeth and James Baumfree, who were slaves on the Hardenbergh plantation. Both the Baumfrees and the Hardenberghs spoke Dutch in their daily lives. After the colonel’s death, ownership of the Baumfrees passed to his son Charles.

After the death of Charles Hardenbergh in 1806, the Baumfrees were separated. Nine-year-old Isabella was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, whose family only spoke English. Isabella still spoke only Dutch, and her new owners beat her repeatedly for not understanding their commands.

When her father came to visit, she pleaded with him to help her. Soon after, Martinus Schryver purchased her for $105. He owned a tavern, and although the atmosphere was crude and morally questionable, it was a safer haven for Isabella.

But a year and a half later, in 1810, Isabella was sold to John Dumont of New Paltz, New York. There she toiled for 17 years. Because of the cruel treatment she suffered at the hands of Dumont and his wife Sally, Isabella learned to speak English quickly, but had a Dutch accent for the rest of her life. It was during this time that she began to find refuge in religion – beginning the habit of praying aloud when scared or hurt.

Family Ties

Around 1815, at age 18 Isabella fell in love with Robert, a slave from a neighboring farm. The two had a daughter, Diana. Robert’s owner forbade the relationship, since Diana and any subsequent children produced by the union would be the property of John Dumont. His owner beat him savagely (“bruising and mangling his head and face”), bound him and dragged him away. Robert and Isabella never saw each other again.

In 1817, Dumont compelled Isabella to marry an older slave named Thomas. Their marriage produced a son, Peter (1822), and two daughters, Elizabeth (1825) and Sophia (1826). Isabella and her husband were promised their freedom for faithful service on July 4, 1826, one year before all adult slaves in New York would be freed by the state. Dumont reneged on his promise.

Free at Last

Isabella was infuriated when Dumont would not allow her to go free, but she continued working until she felt she had done enough to satisfy her sense of obligation to him – spinning 100 pounds of wool. She then escaped before dawn with her infant daughter Sophia. She later said: “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.”

Isabella wandered, not sure where she was going, and prayed for direction until she arrived at the home of white Methodists Isaac and Maria Van Wagener. Soon after, Dumont arrived, insisting she come back and threatening to take her baby when she refused. Isaac offered to buy her services for $20 until the state emancipation took effect, which Dumont accepted.

Soon thereafter Isabella learned that her five-year-old son Peter had been sold into slavery in Alabama. A friend directed her to activist Quakers, who helped her make an official complaint in court. After months of legal proceedings, Peter was returned to her, scarred and abused but alive. The case was one of the first in which a black woman successfully challenged a white man in a United States court.

During her time with the Van Wagenens, Isabella had a life-changing religious experience – becoming “overwhelmed with the greatness of the Divine presence” and inspired to preach. She began attending the local Methodist church, and in 1829, left Ulster County with a white evangelical teacher named Miss Gear.

In 1829 Isabella moved to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Christian evangelist Elijah Pierson and lived among a community of Methodist Perfectionists, who met outside of the church for ecstatic worship. Pierson treated her as a spiritual equal and encouraged her to preach.

Through the perfectionists, Isabella fell under the spell of Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias, for whom she also worked as a domestic. Matthews had a growing reputation as a con man, and Isabella lived with his cult from 1833 to 1834, with the activities becoming increasingly bizarre. Shortly after Isabella changed households, Elijah Pierson died, and Matthews and Isabella were accused of poisoning Pierson in order to benefit from his personal fortune. Both were acquitted.

While living in New York, Isabella attended the many camp meetings held around the city, and she quickly became known as a remarkable preacher whose influence “was miraculous.” In 1843, she was “called in spirit,” and the spirit instructed her to leave New York and travel east to lecture under the name Sojourner Truth. The name signified her role as an itinerant preacher, her preoccupation with truth and justice, and her mission to teach people “to embrace Jesus, and refrain from sin.”

In 1844, Sojourner Truth joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Northampton, Massachusetts. This group of 210 members lived on 500 acres of farmland, raising livestock, running grist and saw mills, and operating a silk factory. Founded by abolitionists, the organization supported a broad range of reforms including women’s rights and pacifism. There she met and worked with leading abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and David Ruggles. Unfortunately, the community was not profitable enough to support itself.

Career in Social Reform

Although the Northampton community disbanded in 1846, Sojourner Truth’s career as an activist was just beginning. She then lived with George Benson, one of the Association’s founders. Since she could not read or write, Truth began dictating her memoirs to Olive Gilbert, another former member. In 1850, Benson’s cotton mill failed and he left Northampton. Truth bought a home there for $300.

Truth began touring with abolitionist George Thompson, speaking to large crowds on the subjects of slavery and human rights. In 1850 William Lloyd Garrison published her memoirs, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave, which detailed her suffering as a slave. It gave her an income and increased her speaking engagements, where she sold copies of the book.

Sojourner Truth traveled extensively as a lecturer after the publication of her book. Her speeches were based on her unique interpretation of the Bible – as a woman and a former slave. She spoke about women’s rights and the abolition of slavery, often giving personal testimony about her experiences as a slave. She was very tall, towering around six feet, and displayed a commanding presence.

Her preaching brought her into contact with abolitionists and women’s rights crusaders, and Truth became a powerful speaker on both subjects. In 1851, she gave a speech at the Ohio Women’s Rights Covention in Akron, Ohio. This is an excerpt from that speech:

… that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

That same year, Sojourner Truth spoke at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. As her reputation grew and the abolition movement gained momentum, she drew increasingly larger and more hospitable audiences. She was one of several escaped slaves, along with Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, to rise to prominence as an abolitionist leader and a testament to the humanity of enslaved people.

Truth toured Ohio from 1851 to 1853, working closely with Marius Robinson to publicize the antislavery movement in the state. Even in abolitionist circles, however, some of Truth’s opinions were considered radical. She sought political equality for all women and chastised the abolitionist community for failing to seek civil rights for black women as well as men. She openly expressed concern that the movement would fizzle after achieving victories for black men, leaving both white and black women without suffrage and other key rights.

Truth later became involved with the popular Spiritualism religious movement of the time, through a group called the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. The group believed in abolition, women’s rights, non-violence and communicating with spirits. In 1857, she sold her house in Northampton and bought a home in Harmonia, Michigan (just west of Battle Creek), to live with the Spiritual community.

Civil War Activism

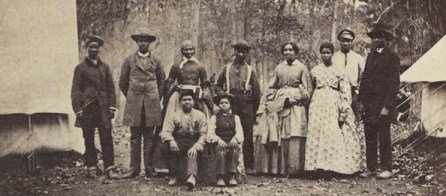

Sojourner Truth put her reputation to work during the Civil War, supporting the Union and helping to recruit black troops for the Union Army. She encouraged her grandson James Caldwell to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, one of the first official African American units. The regiment gained recognition on July 18, 1863, when it led an assault on Fort Wagner near Charleston, South Carolina, where its commanding officer, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, and 29 of his men were killed.

In 1863, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s article “The Libyan Sibyl,” a romanticized description of Sojourner Truth, appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. In 1864, Truth worked with the National Freedman’s Relief Association in Washington, DC. On at least one occasion, she met with President Abraham Lincoln. She also worked among freed slaves at a government refugee camp on an island in Virginia.

True to her broad reform ideals, Truth continued to agitate for change even after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. She took up the issue of women’s suffrage. She was befriended by suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but disagreed with them on some issues, most notably Stanton’s threat that she would not support the black vote if women were denied it.

After the Civil War ended, she continued working to help the newly freed slaves through the Freedman’s Relief Association, then the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington. In 1867, she moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek, converting William Merritt’s “barn” into a house, for which he gave her the deed four years later.

Sojourner Truth Memorial

In Florence, Massachusetts

Later Years

In 1870, Sojourner Truth began campaigning for the federal government to provide former slaves with land in the “new West.” In 1874, after touring with her grandson Sammy Banks, he fell ill and she developed ulcers on her leg. Sammy died after an operation. She was successfully treated by veterinarian Dr. Orville Guiteau, and headed off on speaking tours again, but had to return home due to illness once more.

The movement to secure land grants for former slaves became a major project of her later life. She argued that ownership of private property, and particularly land, would give African Americans self-sufficiency and free them from a kind of indentured servitude to wealthy landowners. Although Truth pursued this goal forcefully for seven years, she was unable to sway Congress.

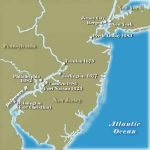

The 1879 spontaneous exodus of tens of thousands of freedpeople from southern states to Kansas was the culmination of one of her most fervent prayers. She spent a year there helping refugees and speaking in white and black churches trying to gain support for the “Exodusters” as they tried to build new lives for themselves. Truth saw the Exodusters, fleeing violence and abuse in the Reconstruction South, as evidence that God had a plan for African Americans.

Truth continuted to make a few appearances around Michigan, speaking about temperance and the need for prison reform in Michigan and across the country. In July of 1883, troubled with ulcers on her legs again, she sought treatment through Dr. John Harvey Kellogg at his famous Battle Creek Sanitarium. It is said he grafted some of his own skin onto her leg.

Until old age intervened, Truth continued to speak passionately against social injustices. She was an outspoken opponent of capital punishment, testifying before the Michigan state legislature against the practice. She also championed prison reform in Michigan and across the country. While always controversial, Truth was embraced by a community of reformers including Amy Post, Wendell Phillips and Lucretia Mott – friends with whom she collaborated until the end of her life.

Sojourner Truth died at her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, on November 26, 1883. She was buried in Battle Creek’s Oak Hill Cemetery alongside to her grandson.

In 1890, Frances Titus, who had published the third edition of Sojourner Truth’s Narrative in 1875 and had served as her traveling companion after Sammy died, collected money and erected a monument at the gravesite, then commissioned artist Frank Courter to paint the meeting of Sojourner Truth and President Lincoln.

SOURCES

Biography.com: Sojourner Truth

This Far by Faith: Sojourner Truth

STA: Sojourner Truth

She is a beautiful and brave woman

Most people are prisoners of the values and morals of the time period in which they lived… Ms Truth transcended her time period with her vision of equality for all Americans.